Tags

Charles Manson, Charlie Says, Film, Hippies, Joan Didion, Manson Murders, Movies, Once Upon a Time in Hollywood, The Sixties

I was born in 1966. I grew up hearing that there was something special about the decade of my birth. What that was, and whether or not it was a good thing was never all that clear. You’d hear different messages from different people, and sometimes even from the same people, but whether they were celebrating the peace and love or griping about the Goddamned hippies, everyone around me seemed back then to agree that something big had happened in the sixties.

But what was it?

And what happened to it?

To hear Hunter S. Thompson tell the story, the Sixties crashed like a wave upon the outskirts of Las Vegas and receded back toward the West Coast. For Joan Didion, or at least for the ‘many people’ she mentions in “The White Album,” the sixties ended on the night of the Manson murders. There are other candidates for the death knell of the sixties, but the issue isn’t simply a break in the pop-culture timeline or the social geography of the nation. Each of these purported breaking points become a kind of lens through which people now view the sixties. Each such post-mortem report is an invitation to see the sixties in a certain way from its beginning to its end. In such stories, the dismal end of the era is always a sour version of its beginning, a spoiled version of some initial promise. We can almost see a trace of free love in the brazen sexuality of modern pornography. The voice of Timothy Leary seems to echo in the background of contemporary drug abuse. We can hear the flaunting of social conventions in the incoherent rantings of an imprisoned Manson. Much of the modern world seems almost to appear as a betrayal of some hope that once flourished in the sixties.

For some people anyway.

Whatever that hope might have been was for older generations, for those who came of age in the midst of the decade, those of us who were literally children of the 60s generally grew up knowing that we had arrived a little too late.

But too late for what?

***

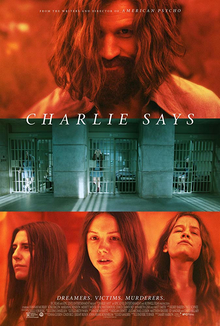

I was thinking about this the other day as I watched Charlie Says. What brought it to mind was…

…

SPOILER ALERT!!!!

…

…the final scene.

As the film ends, Leslie Van Houten, or ‘Lulu’ as Charlie dubbed her, sits in her cell reflecting her time with Manson. Having finally come to the realization that her violent crimes were all for nothing, She recalls a moment in her life, a time when a biker showed up to take her out of the Spawn Ranch, away from Manson and his control, and of course, well away from the crimes she would later commit on his behalf. As this event actually unfolded, so the movie tells us, Van Houten told the biker she wanted to stay and he rode off without her. In that final scene Van Houten imagines she’d taken him up on it; she imagines herself climbing on the back of his bike and resting her face against his back, sunlight shining down on her cheeks as he rides her off to safety and away from a life lived in the wake of a notorious crime. It’s a vision of freedom.

It was a freedom she did not have the courage to claim when she had the chance.

We watch that freedom slipping away from Van Houten throughout the movie as Manson turned free love into sexual domination, and freedom from the rules of civilization into life lived by his rules and his whims. We see her lose that freedom in stages, always drawn in further by the promise of it. The freedom from conventional culture seems to haunt the entire movie in much the same way that the entire decade haunts the popular culture today. Van Houton seemed to be chasing the ever-elusive sixties the entire time she spent with the Manson family.

…only to missed it completely.

Of course, this isn’t actually a story about the 60s; it’s a story about Lulu, a young woman who never achieved the ideals she might have hoped for, even as she dove whole-heartedly into the values and cultural motifs of the era. In the end, Van Houten is left dreaming of the freedom she once sought from within the confines a prison cell.

Leslie Van Houten is iconic figure of the era, a woman so intimately connected to the sixties, her story is bound to come up whenever people today speak of the decade, but her significance is as perverse as it is tragic. She is for ‘many people’ the death of that very era, so Didion tells us. But it’s the death of something never fully realized in the first place. The sixties rest always a little beyond the events of her life, out of reach, and receding ever further from reach the harder she and her companions tried to reach it.

We could of course think of it as a story about Leslie Van Houten and the rest of the Manson family.

It could just be that.

But it’s also a meditation on the sixties itself.

And in this story, the sixties never become real. The decade appears as a false promise in moment after moment of the story. It ends as an idle fantasy of a woman who ruined her life and that of many others in pursuit of that very fantasy.

***

I can’t help but to compare this fantasy sequence to that of “Once Upon a Time in Hollywood.” If “Charlie Says” ends on a fantasy sequence, the fantasy-sequence in Tarantino’s story runs for the whole length of the film. It too indulges in an exercise of wish-fulfillment, and it too uses that exercise to say something about the sixties.

For Tarantino this is a conflict between old Hollywood and the counter-culture. His heroes have little but contempt for the hippies they encounter, and it isn’t because they know these particular hippies will become murderers. No. their contempt echoes that of so many middle Americans for whom the lifestyle of the counter-culture was sufficient to trigger all the contempt they could muster. Sure, Tarantino’s protagonists might have had some use for the free love, and they could even try a drug or two, but they were never going to embrace these things as a way of life. No, the drug of choice for conventional Americans was always liquor (and of course Mama’s Little Helper), and free love was just an opportunity to get laid. The sixties might have posed a few extra thrills, but for so much of America, it was also a genuine threat to very lifestyle in which such thrills might make sense to people. This was the response that so much of America had to the sixties; and it’s the attitude of the main characters in Once Upon a Time in Hollywood.

Whatever ideals the hippies of this era might have pursued, they were of little or no consequence to the lives of Tarantino’s fictional Hollywood star and his stuntman sidekick. To them, hippies were a source of annoyance (if also fascination). They seemed to see the sixties through the lens of the fifties, as a possible threat to the establishment. As men whose livelihood was tied to the old Hollywood movie system, these characters were hardly going to support any revolution.

Violent or otherwise.

But of course the fantasy in this film is incredibly violent. Once Upon a Time in Hollywood invites us to imagine an answer to the real life violence of the Manson murders in the form of a classic Hollywood formula. What do you do about people like the Manson family? Well, a Hollywood stuntman beats the shit out of them, before the star comes in to finish the scene.

If Tarantino has any doubts about the authenticity of the Manson family as symbols of the sixties, he doesn’t seem to raise them, not in this film. His stars accept the Manson family as perfectly suitable representatives of the hippie-subculture. In killing them, the stars not only save the lives of Sharon Tate and other victims, they crush the hopes and dreams of the counter-culture movement and vindicate the conventional dreams of middle America.

There is something particularly fitting in the notion that a Hollywood star and his stuntman could be the answer to the real-life killing of a famous actress and her companions.

It’s a poetry of sorts.

If we can imagine what the sixties might have meant to Leslie Van Houten in Charlie Says, the question is hardly relevant to the story in Once Upon a Time in Hollywood. Van Houten won’t even be there at the end of the story to contemplate her mistakes.

Whatever promise the sixties might have meant to anyone, it was of little concern to the characters in Once Upon a Time in Hollywood. Their hopes and dreams had been framed in the 50s, at the height of the post-war boom. To them, the sixties were a threat that walked up the street and entered the wrong house for no good reason.

That threat died at the business end of DeCaprio’s flame thrower.

What I remember most about the 60s was the music. It was an interesting time. It was also the assassination of the Kennedy brothers and Martin Luther King. Those murders had nothing to do with counter-culture. My little sliver of counter-culture was an intense desire for peace and understanding between all kinds of different people. And yeah, we all learned how to get laid.

Good post. Bookmarking it to think about later.

Very thoughtful and interesting post — thank you!

I have some years on you, and clearly recall the optimism of 60s counterculture. That optimism was almost inevitable as an outgrowth of the relative safety of the 1950s Eisenhower years. In the 1950s, white middle-class America had was almost smug in its sense of self-righteousness — which the counterculture punctured. That conflict is what informs the characters’ attitudes in Tarantino’s film.

For most of my friends (and me) the 60s did not end with the Tate-La Bianca murders; it ended at Altamont. For many reasons.

Again, many thanks for this post!

It’s funny I saw this blog post today. A couple of days ago I was listening to Ohio by CSNY and I had the thought that we’re now living in similar times but it doesn’t seem as flashy now as it did then. Now I’m pissed off and terrified.