Tags

Death, DnD, Dungeons and Dragons, Friends, Games, Non Player Characters, Nostalgia, Role Playing Games, RPGs

Eleymenen, The Murder Mage, wasn’t supposed to be a recurrent NPC, let alone my go-to villain for countless D&D campaigns. He had his birth in a simple premise. a small party of first level characters would get caught between two high level spell-casters blasting away at each other in a town market. This was first edition D&D, and I made him up under the clunky old rule for dual-classed characters. As I recall, I made him an 8th level Assassin and a 5th or 6th level Magic User. Had he meant to attack the player characters, Eleymenen would have slaughtered them easily, but that wasn’t the premise. He and another spell caster went to war with each other. The players just had to get out of the way, perhaps overcoming a minion or two on the way out of the area. They managed fine.

In any event, Elemenen survived the battle.

It seemed a good move to bring him back a few games later, this time to attack the players directly. I thought he’d be a recurrent baddy for a game or two before they killed him off and moved on to the next stage of the campaign. Instead, Eleymenen became a persistent nuisance to one campaign after another, growing in time to become a virtual demigod with unimaginable powers. The last time I hauled him out, he was still an 8th-level assassin of course, but he was at least a 22nd-level Magic User. My players were so sick of him.

I definitely overdid it.

But this isn’t a post about Eleymenen.

***

It’s a post about my old players.

What got me thinking about them was a decision to revise Eleymenen for my current home-brew game, perhaps to put him up against a new group of players.

I suppose I should have known working on Eleymenen would bring back old memories. The thing is, most of the players who struggled against this NPC back in the day are now gone. They aren’t around to gripe when he makes another appearance on the game table. I won’t hear their jokes, or even their complaints. I won’t get to see them wallow in despair at the mere mention of his name or plot against him one more time, and I won’t get a chance to give them that final victory, the one they earned several times over, so very long ago. It seems trivial enough, but I should have given it to them, that final victory. I should have let my players kill-off this guy for good way back in the 80s.

It’s too late now.

It’s a trivial thing, the death of an NPC.

It’s not a trivial thing, the passing of old friends.

At this particular moment, I find the two themes blend rather seamlessly together.

***

As a high school kid, back in the 80s, I always assumed I would one day stop playing RPGs. It just seemed like it would come naturally, a regular part of growing up. I was pleasantly surprised to find myself playing D&D all through college, a little more surprised to find myself playing it on and off through grad school, and very surprised to find myself still playing RPGs in my 30s and 40s. A few of my old players were still with me. Others had dropped out of the gaming world. But there were always new players. Well into my 50s at this point, I am no longer surprised to be playing these games, or even to find others my age still attempting to slay dragons with odd shaped dice and an arsenal of bad jokes.

Hell, I expect to kill orcs in the old folks home, if I make it that far.

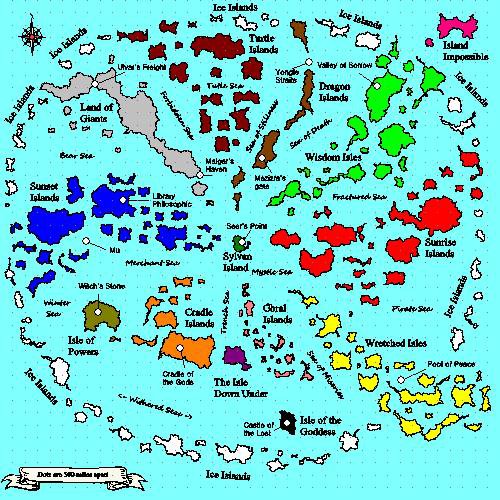

What I never really thought about was the sense of loss that gaming sometimes brings to mind in the absence of old friends. I suppose I might feel this less if I hadn’t kept my games to a pretty consistent setting or if I hadn’t played with some of the same people for decades. Most of our campaigns took place in one or two different worlds. Old characters made frequent appearances, and steady players often got to bring a ringer into new campaigns. At one point, I realized my old characters were old enough to vote. So were those of my long-time players. These characters and their storylines were persistent enough to leave an impression.

In any event, the absence of these old plot-points and the players behind them is a growing part of my gaming experience. I can’t help but think of my old friends while sitting down to a game these days.

I know that I will never again experience the frustration of Andy’s efforts to derail the entire premise for a game session, never see him burn down a city instead of fighting his way into a building, which was the challenge I meant to set up. I won’t hear him badger me over a frustrating call, nor will I fight with him over the best dice at the table or the last good pencil in the house. I won’t marvel at his min-maxing skills or grumble over how late he was to a game session. I won’t cringe as he accidentally kills other player characters with errant fireballs. I won’t get to taunt Chuck with threats against a custom character or curse as he and Dan both team up to betray the entire party in the middle of a close battle. I won’t even get to laugh at Dan as his fighter spends an entire game session putting on his plate armor while everyone else has the fight of their lives. These moments and many likely them are mostly gone now. With a few exceptions, I am the only one who remembers them. There are few left to reminisce about these old memories. They are trivial because they are no more than a game, and they are profound because they are links to people I’ve known and loved.

“Remember when…” mostly falls on deaf ears now.

That does feel a bit lonely.

Still, there is a certain pleasure in knowing that the Pox Hounds I will attack us with sometime next month are all descended from one of Chuck’s old characters, or that the house rule for hand-and-a-half weapons came from Andy, a simple solution to a problem we batted around for months. My new players don’t know what it means to be the Russ of the campaign, nor will anyone know that my House-rules for GM’s characters come from Will, or that Will broke those house-rules all the Goddamned time. The next player to wear a suit of Sealy Posturepedic armor will probably never know about the story of Dan’s fighter and the great battle he missed, but that player will appreciate the chance to sleep in the comfort of some fine magical armor. And I will smile every time I think about it.

***

It’s an odd thing. When close friends and family pass, they always take a little of us with them. Memories once shared with others become personal matters. You can share the stories with other people, of course, but they will never resonate with anyone else the way they once did with those who shared the experience.

And who but a gamer would give a damn!

This happens in real life.

It also happens in the game world.

As long-time gamer friends pass away, they take away a little bit of the worlds you’ve shared with them, pieces of the stories you once told together. You can see traces of your old gamer friends in a house-rule, a recycled challenge, or even the design of a custom magic-item that had all of you laughing at one time or another. You hear them in the silence of an inside joke nobody laughs at anymore. You smile at them as you realize how they would have responded to a new challenge.

Players who moved away or simply quit gaming are one thing. You may one day talk to them again, perhaps even about the times you once shared rolling dice. That possibility alone keeps their memories light, but those who’ve passed away leave shadows on the worlds you’ve built together. Some days you feel that with more intensity than others.

Like when you decide to resurrect an old villain, for instance.

It seems odd to think of a game as something that carries so much weight, but this is just one of many ways that the lines between the fantasy framework of a game and the social networks of real life become blurred. When friends leave, they often leave a mark. When those friends shared an imaginary world with you, they often leave a very real mark in that imaginary world.

***

I’ll be thinking about my old friends when I put Eleymenen back on the table to make life difficult for my new friends. They won’t know what’s up, the new group, I mean. To them, he will just be a particularly challenging boss villain, whereas he is in fact a sort of haunted character.

Very haunted.

Just not by anything in the game rules.

This last weekend, I enjoyed a few rounds of beer along with a few rounds of one of my favorite games, “Unexploded Cow,” by Cheepass Games. It’s a great game, especially for anyone well into their cups. The game is just predictable enough to lend itself to a little strategy, but not so predictable that victory will always go to the better player. You can try, but you can’t really count on winning, so the important point is to sneak a bad cow into the herd of someone you love, have another brew, and enjoy talking trash to literally everyone at the table.

This last weekend, I enjoyed a few rounds of beer along with a few rounds of one of my favorite games, “Unexploded Cow,” by Cheepass Games. It’s a great game, especially for anyone well into their cups. The game is just predictable enough to lend itself to a little strategy, but not so predictable that victory will always go to the better player. You can try, but you can’t really count on winning, so the important point is to sneak a bad cow into the herd of someone you love, have another brew, and enjoy talking trash to literally everyone at the table.

I think most of us who play RPGs have had this experience, the one where the game master (GM) brings in a ringer. It may be a non-player character (NPC), or it may be the GM’s own personal player character (PC, which was much more common back in 1st edition, …yes, I’m that old). Either way, the ringer towers over the player characters. He kicks ass while they struggle to make a difference.

I think most of us who play RPGs have had this experience, the one where the game master (GM) brings in a ringer. It may be a non-player character (NPC), or it may be the GM’s own personal player character (PC, which was much more common back in 1st edition, …yes, I’m that old). Either way, the ringer towers over the player characters. He kicks ass while they struggle to make a difference. Back in the days of first edition, a GM’s player character was most often rolled up according to the same rules as those of the players. This provided a bit of a check on the whole ringer problem. Abuse could still happen, but there was a bit more of a sense that the GM’s character was supposed to be part of an ensemble. When they come in over-powered to begin with, they inevitably become the star of the show, and the notion that a given character isn’t really a player character can very well serve as the excuse for a GM to field one who simply dwarfs anything the other players can produce.

Back in the days of first edition, a GM’s player character was most often rolled up according to the same rules as those of the players. This provided a bit of a check on the whole ringer problem. Abuse could still happen, but there was a bit more of a sense that the GM’s character was supposed to be part of an ensemble. When they come in over-powered to begin with, they inevitably become the star of the show, and the notion that a given character isn’t really a player character can very well serve as the excuse for a GM to field one who simply dwarfs anything the other players can produce. I can think of a few angles. Whether or not they would actually add up to a fun campaign, well that’s an open question! Anyway, here are the guidelines I would use to set up the campaign.

I can think of a few angles. Whether or not they would actually add up to a fun campaign, well that’s an open question! Anyway, here are the guidelines I would use to set up the campaign. Three: Let a player run the ringer. I’ve done this countless times. My old first edition D&D campaign ran for over 20 years. Since we started a new plot-line every year or so, we would often roll one or of the old characters into the new campaign. This often meant that a single player would have a 9th level character or two while everyone else was starting at 1st. It could be fun. We let different players run the ringers in different campaigns, and with multiple characters on the board, no-one got bored. There was always plenty for the other characters to do.

Three: Let a player run the ringer. I’ve done this countless times. My old first edition D&D campaign ran for over 20 years. Since we started a new plot-line every year or so, we would often roll one or of the old characters into the new campaign. This often meant that a single player would have a 9th level character or two while everyone else was starting at 1st. It could be fun. We let different players run the ringers in different campaigns, and with multiple characters on the board, no-one got bored. There was always plenty for the other characters to do. Five: You can give the player characters independent tasks and even long-term goals that diverge slightly from those of the ringer. Perhaps, the ringer is happy to demolish all the orcs in the northern wastelands, but she isn’t all that concerned about the elven princess the characters want to keep alive. Their challenge thus requires tasks that the ringer won’t help with and their sense of accomplishment will then rest (at least partially) on terms that don’t involve the ringer.

Five: You can give the player characters independent tasks and even long-term goals that diverge slightly from those of the ringer. Perhaps, the ringer is happy to demolish all the orcs in the northern wastelands, but she isn’t all that concerned about the elven princess the characters want to keep alive. Their challenge thus requires tasks that the ringer won’t help with and their sense of accomplishment will then rest (at least partially) on terms that don’t involve the ringer.