Tags

Canada, Climate Change, Inuit, Markets, Metaphor, Mother Earth, People of a Feather, Primal Gaia, Science

I’ve been thinking lately about the notion of Mother Earth (or Primal Gaia). She figures rather prominently in a lot of the literature I read back in grad school, and I frequently have occasion to revisit some of that material with my students. What has me thinking about this lately is a few discussions on the topic of climate change initiated by a colleague of mine. So, like I said, …I’ve been thinking about her lately.

I’ve been thinking lately about the notion of Mother Earth (or Primal Gaia). She figures rather prominently in a lot of the literature I read back in grad school, and I frequently have occasion to revisit some of that material with my students. What has me thinking about this lately is a few discussions on the topic of climate change initiated by a colleague of mine. So, like I said, …I’ve been thinking about her lately.

To say that I find it hard to believe in such an entity is putting it mildly. I don’t literally believe that the earth itself has a will of its own. Even still, I can’t help thinking the notion of Mother Earth has a lot going for it. Near as I can tell, talk of Mother Earth conveys two things about the environment that are all easily lost in Her absence.

The first entailment is a sense of dialogue (or perhaps dialectic) in nature. So long as we think of the world around us in terms of objective data it becomes that much easier to anticipate the consequences of our own actions in terms of an essentially cause and effect sequence. We may recognize that some of the effects of our actions escape us at the moment, but that just doesn’t stop folks from thinking of their actions in terms of a discrete cause and effect sequence based on our present understanding of the world at hand. If I do x, the result is y. That seems to be how people think about objects.

Not other people!

Subjects.

People (and most living things) can be predictable, to sure, but they are never entirely so. My cat is meowing at me as I type this. I expect she will bring me a toy to play in a moment. That’s what I expect her to do, but she may surprise me. Likewise, I may surprise her. Maybe this time I won’t stop typing and toss the toy about for her to chase it. Likewise, my students may not do the assignments I give them; my boss may not count my workload as I expected; and the folks at Amazon may not package my latest order of chili paste as they have so many times in the past. Living things…

(Pardon me. I’ll be back in a moment.)

(Pardon me. I’ll be back in a moment.)

…

..

.

Anyway!

As I was saying, living things always seem to add something else to the mix when they react to our own behavior. Sometimes, they even start things of their own accord. Therein lies one of the real advantages to thinking of the environment in terms like those suggested by terms like “Mother Earth.” It gets us out of the habit of thinking that we know exactly what She is going to do. …of thinking that the concrete effects we hope to bring about with any given action ever come close to a thorough account of our impact on the world around us. I can think my way to this bit of humility, but talk of Mother Earth suggests that notion from the very outset. If I think of the earth as a living thing, I don’t have to remind myself that burning carbon-based fuels may have unintended consequences. I can be sure of it. In this context and others, I can be sure that Mother Earth will always add something to the mix when she responds to me and others.

Oh sure, we can conceive of particular things in terms of fairly discrete cause&effect relationships. If I leave a Cocacola outside, it’s going to freeze and burst. Hit a ball with a bat and it will fly away.Better yet, hit a cue ball low with a well-chalked cue-stick and it will (hopefully) spin backwards after contacting the object ball. These are things we can imagine in relatively specific terms. But as our account of the object world expands, as we approach aggregate subject matter such as an ecological niche or regional environments, our ability to conceive of things in such neat terms starts to fall apart. Which is precisely what makes the notion of Earth as a subject in Her own right becomes a rather tempting option.

But I did say that the notion of Mother Earth conveys at least two things about the physical environment, didn’t I? Well the second is pretty simple. Thinking of earth as our Mother effectively conveys a sense of nurturing. More to the point, it conveys a sense that we are the ones being nurtured, and that we are dependent on her. Since She is a person, rather than a thing, or even a collection of things, this means we are dependent on Her good will.

The upshot of all this is a kind a moral responsibility, a sense that life itself entails a moral responsibility to earn the good will of the world that makes our lives possible. We could get to that sense of moral responsibility in other ways (even stewardship, perhaps), but I don’t know of any ideas that convey it quite so effectively as notions like those of Mother Earth or Primal Gaia.

For me , at least, She may be little but a metaphor, but for a metaphor, Mother Earth can be damned compelling.

***

So, what has me thinking about this tonight? A film called People of a Feather. This documentary follows the efforts of an Inuit community dwelling on the shores of Hudson Bay (near the Belcher Islands)as to learn why the local population of Eider ducks is in serious decline. Following substantial die-offs in the 1990s, they asked the Canadian Wildlife Service for help in determining the cause. What they got in the way of help was Joel Heath, an ecologist who documented his years of research in this film.

So, what has me thinking about this tonight? A film called People of a Feather. This documentary follows the efforts of an Inuit community dwelling on the shores of Hudson Bay (near the Belcher Islands)as to learn why the local population of Eider ducks is in serious decline. Following substantial die-offs in the 1990s, they asked the Canadian Wildlife Service for help in determining the cause. What they got in the way of help was Joel Heath, an ecologist who documented his years of research in this film.

This is a gorgeous film. Heath’s underwater footage of Eider ducks swimming about in search of shellfish is absolutely spectacular. He also spends a good deal of time documenting the lives of local Inuit and filming the cycles of surface ice on Hudson’s Bay. One of the things I like most about this film is the way Heath leaves much of the detail without comments. He simply lets his camera linger on the scene and leaves us to piece together the details for ourselves. If Heath has done his job well, and he has, the footage alone is often enough to tell a story in its own right.

What the film does take the time to explain is just what is happening to stress the Eider ducks in this region of Hudson Bay. It’s worth knowing at the outset that these ducks do not migrate. Instead, they spend the winter along small patches of open water called Polynyas. The problem of course is that something is happening to the Polynyas. They have become significantly more unstable in the 2000s, effectively leaving the ducks without a dependable means of surviving the winters.

So, why is this happening? The simple answer is that the hydro-electrical systems used to heat the major cities of Canada have altered the currents (along with the salinity) of the bay. The Hydro-electric dams in the region typically release large amounts of fresh water into the bay during the winter, effectively reversing the normal cycles of activity. The increasing instability of the polynyas may be just the tip of the iceberg here (ironic metaphor, I know). Heath’s work, and that of his Inuit friends thus raises questions about the total long range-impact of the power-grids used to support the mainstream communities of Canada. As people who rely on the natural cycles of the region to support themselves, the Inuit who initiated this research are felling the effects more directly than those living in the cities, but this is small comfort to anyone contemplating the long-term consequences of changes in the water system of the region. In effect, the eider ducks may have been a bit of a miner’s canary. Things are happening in the area that no-one really anticipated, and the questions are how much change will the hydro-electric systems brings about? How much will they be allowed to bring about? Are there alternatives?

People of a Feather doesn’t really answer these questions, though Heath does outline a few brief policy considerations as the credits roll. What makes this film great, however, is his patient development of the problem itself, and in particular his ability to help us understand just what this problem means to the Inuit living the area, Inuit who (it must be emphasized) saw fit to initiate the study itself and provided active support throughout its development.

This is one of those times when indigenous people got the details right. It’s a story of indigenous people working closely with scientists to address an important question about the natural environment. I’m reminded of similar efforts to improve the accuracy of whale counts along the coast of the North Slope here in Barrow. When scientists and Inupiat whalers disagreed about the number of bowhead whales in local waters , both groups devised new means of counting the whales. Turns out the Inupiat were right. (You can read about it in The Whale and the Super Computer by Charles Wohlforth.) Simply put, it pays to listen when indigenous communities raise concerns about what’s happening in the local environment. They don’t just give us grand abstractions like Mother Earth and poetic themes for movies, poems, and pastel-laden paintings. Sometimes, they really do provide the best resources for understanding particular things.

That said, I do find myself wondering about the story-line presented in People of a Feather. It’s not the most heavy-handed narrative, to be sure, but in this film it would be fair to suggest the hydro-electric dams appear to be the source of evil, so to speak. That isn’t because the people producing them mean to hurt anyone. It really isn’t. Rather, the problem is an unintended consequence of their function, a consequence felt most particularly by an indigenous population whose livelihood is determined as much by the natural cycles of Hudson’s Bay as it is by those of the modern market. Which reminds me of other narratives that could be told of this same issue, narratives about progress and development, of carving a civilization out of the frozen wilderness. These are the narratives that will be more familiar to people living closer to those power grids, and to most I suspect that will read this blog post. In these narratives, the dams are good thing, almost a miracle, one that makes possible the lives of countless people. We could probably even point to a few benefits enjoyed by those in various indigenous communities. Those connections are there. How we sort the details, and what people want to do about them is another question. My point is that these grand narratives tend to predetermine the significance of the facts. It may not even be that the policy-considerations demand a choice of one value or another, but in the stories people tell about this such an issue the choice is often already made by time the plot starts to quicken.

…which may be the reason this film has me thinking about Mother Earth. This is one more instance in which something people didn’t anticipate turned out to be critical to the lives of some people (and some ducks). It’s also one case in which people have begun to sort those consequences out, just as we hope to be doing with issues like global, ocean acidification, and so many other issues in which the natural environment as a whole seems to be threatened, and along with it, us. Yet our understanding of these issues is always playing catch-up to the processes we’ve initiated, and frankly, it isn’t clear that this understanding is catching up fast enough. It’s enough to make us wish we had a way of talking about these issues that reminded us from the outset of just how much we don’t know about the impact of humans on the environment.

The temptation to call for Mother aside, it’s worth noting that comparable metaphors typically guide popular thinking (and policy) on the subject as it stands. Here I am speaking of the invisible hand of the market. Hell, the very notion of a market is a bit of a metaphor, an image that transforms known tendencies, tendencies with variable strength and effective) into a kind of thing that we can depend on. Do people in cold climates want a means of keeping warm? Supply will rise to meet the demand. The market will sort its way to a kind of equilibrium. One could easily apply such thinking to the process which puts all those dams on Hudson’s Bay to begin with, and it would help us to understand a few things. But this thinking too relies on the turn of a metaphor, and it too seems to distorts the facts in a few subtle ways.

One of the most interesting things about the invisible hand of the market deity is just how effectively it can be used to remind us of just how little we know about the economic impact of government policies. Time and again, market theorists remind us that each and every regulation (such as laws mitigating fresh water release in the Canadian hydro-electic system) will have unanticipated consequences. Time and again, free market fundamentalists will tell us to be wary of efforts to correct social ills. We may just make them worse! They are right, of course, except on the main point, because those truly devoted to this metaphor consistently tell us to let the market work itself out. It’s easy to think of this as a kind of humility, a recognition that being mere mortals, human beings cannot anticipate all the consequences of our own actions. The problem of course is that free market fundamentalists will only carry this logic as far as the market itself. How those unintended consequences will affect the balance of human relations to the environment is typically beyond the scope of their reckoning. Any humility we may learn from tales of the invisible hand seems ironically to leave us with an odd certainty in its own right, a mandate to leave unquestioned most anything done in the name of profit. For a lesson in humility, this takes us to a place that looks awful lot like hubris.

Stories of the invisible hand bid us to exercise caution less the market come back to bite us for every effort to legislate our way to a better world. They don’t do much to address the externalities piling up in the environment around us. In vie of these externalities, it is becoming increasingly clear that just about every cost-benefit analysis ever computed in human history has fallen short of a proper reckoning. I don’t see an adequate account of this coming from those devoted to the image of the invisible hand. If such is to be had, it will either come from painstaking empirical research, or from the language of another metaphor entirely.

***

…a trailer for you!

There is one other thing I really must say about the Nevada State Museum, and that it that it seems to contain the White Tree of Gondor. Oh, they call it a Great Basin Bristle Cone Pine, but I know the White Tree of Gondor when I see it. You can’t fool me!

There is one other thing I really must say about the Nevada State Museum, and that it that it seems to contain the White Tree of Gondor. Oh, they call it a Great Basin Bristle Cone Pine, but I know the White Tree of Gondor when I see it. You can’t fool me!

Aside from being

Aside from being  Last week a man named Trebor Gordon, Pastor for the Harris County GOP, tried to block a Muslim, Syed Ali, from serving as a precinct chair for the Republican Party in Harris County, Texas. As reported in

Last week a man named Trebor Gordon, Pastor for the Harris County GOP, tried to block a Muslim, Syed Ali, from serving as a precinct chair for the Republican Party in Harris County, Texas. As reported in

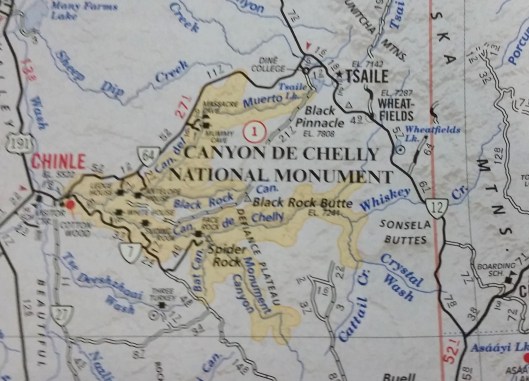

If you are traveling around the four-corners, you might think your best bet for a map would be one covering one or more of those states.

If you are traveling around the four-corners, you might think your best bet for a map would be one covering one or more of those states.

The Revenant was cool. In fact it was damned cool!

The Revenant was cool. In fact it was damned cool!