Tags

American History, American Indian, Custer, George Armstrong Custer, History, Indigenous Peoples, Little Bighorn, Native American, Semantics

I believe I was in college when I first had someone tell me I shouldn’t use the word ‘Indian.’ I had certainly heard plenty of critical commentary about Christopher Columbus, and at least some of that commentary had included a remark or two on the absurdity of applying the word ‘Indian’ to the indigenous population of the Americas. Still, in the lily-white neighborhoods of my upbringing, this word became just another absurdity in a world that already had plenty of them. So, when my Navajo classmate, Wendy, expressed a clear preference for ‘Native American,’ this was new. What was new about it wasn’t the critique of the word ‘Indian’; it was the sense that the critique mattered.

I wish I could say that I responded appropriately, but I’m afraid I can’t.

There was whitesplaining; let’s just leave it at that.

***

Admittedly, the rest of this post could qualify as more of the same. I hope not, but we’ll see…

***

I’ve heard a couple of interesting theories about the origin of the term, ‘Indian,’ but I’m not sure that any of them have really nailed down the concept. Origins are not the only rubric by which we might assess the meaning of a term, and folk-etymologies are infamously inaccurate, so the whole question of where the word came from has to be taken with a grain of salt.

Anyway…

The notion that Columbus thought he was in India is an incorrect correction, at best. Columbus thought he was in the East Indies. That may sound like a fussy point to make, but folks ought not to point out one mistake only to land on another. Somewhere in his work, the historian of religion, Sam Gill, suggests that Europeans used the term ‘Indian’ (or ‘indios’) as a kind of catch-all category for everyone who lived east of the Indus River. By this account, the problem with the term is not so much a clear factual error as a kind of vagueness, that and a kind of projection of the European imagination into new territory. It’s not at all unlike those associated with ‘orientalism’ in other historical contexts.

Another interesting take comes from the noted activist, Russell Means. According to Means, the term originally meant “‘under God,’ thus making it an accurate observation of the spirituality of America’s indigenous peoples. At a time when many were switching from ‘Indian’ to ‘Native American,’ Means embraced ‘Indian,’ even insisted upon it. Of course, this may have had something to do with branding. Means was of course a long-time member of “The American Indian Movement (AIM),” which might have given him a little extra reason to hold onto the label. In the end, it seems that most of those seeking to refer to the indigenous peoples of North America with a degree of respect have shifted to ‘Native American.’ Mileage always varies, but ‘Native American’ seems to be the norm at this point.

***

I am occasionally reminded that there is at least one problem with ‘Indian’ that “Native American’ does not solve, that is the vagueness of such a catch-all term. This vagueness facilitates a range of problematic thinking. For example, I lost track of the people who asked me if I lived in a teepee while I was living on the Navajo Nation. The Navajo people had never lived in teepees, but the imagination of the American public (and the world at large) often puts them in teepees for the same reason that it put so many peoples from the great plains in Monument Valley for so many classic westerns. To the public at large, an ‘Indian’ is an Indian, and because we can use the same word for so many peoples they think the word must tell us something about all those people. That the term is really little more than a default category for a broad range of people doesn’t seem to enter folks thinking, at least not without first giving them a verbal shove in the right direction. Still, to the degree that this is a problem with ‘Indian’ that problem is not much improved by saying ‘Native American.’ People can infer far too much from “Native American” just as they do “Indian.” It might be more polite to use the former, but it doesn’t do much to improve the understanding.

Since I began focusing on Native American studies in grad school, I have had a couple friends and family ask me what “Indians believed” about topics like God, reincarnation, or the afterlife in general. Today, I am sometimes asked what ‘Native Americans’ think about the same topics, and the foolishness of the question is not changed in the slightest by the more respectful label. I often find myself responding to these questions by asking which tribe? Others might ask them why they are asking these questions of a white guy? In any event, the problems with such questions are not much improved by the change in vocabulary. Whichever word we might use, the question assumes implications that just aren’t there.

***

I happened into an interesting illustration of the problem one day while surfing travel blogs. One of these had a lovely account of a couple’s visit to the National Monument at Little Bighorn Battlefield. Their account was thoughtful and respectful, and I do not mean to direct negative attention their way (and in any event, I can no longer find it, hence the lack of a link), but one thing about their post stuck out in my mind. They made a point to say that their tour guide had been a student at the nearby Little Bighorn College, a tribal college, so they had gotten “the Native American point of view” on the battle. (I believe I got the quote right, but in any event, that was certainly the gist of it.)

Why is that a problem?

When people address the significance of the Battle of Little Bighorn (or Greasy Grass) to Native Americans, they are usually thinking in terms of those who fought against Custer and his troops. That would be Cheyenne and Lakota for the most part, (though there were some Arapaho in the village too.) I can’t help but think, those who read the blog in question will naturally think the “Native American” perspective mentioned in the blog will reflect the point of view of those peoples, but Little Bighorn College is on the Crow Agency, and the student in question was very likely Crow. His ancestors probably didn’t fight Custer on that day. In fact, some of them were likely serving as Custer’s scouts. To the degree that his or her native identity may have shaped the story these bloggers heard, it is unlikely that it was shaped in the manner most readers would have imagined.

Now, I certainly do not mean to suggest that a Crow’s perspective on the battle of Little Bighorn should weigh less than that of a Cheyenne or Lakota, not in the slightest. What I am suggesting is that the difference in this case matters. There is a difference between the perspective of someone whose ancestors fought against Custer and someone whose ancestors allied themselves with him. That difference is easily obscured when using terms like ‘Native American’ or ‘Indian.’

…which reminds me of one discussion I had about these issues with my own students at Diné College on the Navajo Nation many years ago. Fed up with my efforts to problematize every term available for the indigenous people at large, one of my own students just asked; “How about Diné?”

…which got us to the end of the lesson about 15 minutes early.

Don’t get me wrong; there are no magic solutions to any of these problems, but some words help us more than others. There are many contexts in which words like “Indian” or “Native American” are tough to avoid, but when you know which specific people you are talking about, it is almost always better to name the indigenous community in question.

It would certainly have been better suited to the particular story told in that travel blog.

***

A few pics from Little Bighorn College.

(Click to embiggen)

A few pics from the Little Bighorn battlefield.

(Click to embiggen)

And a couple random pics from around the area.

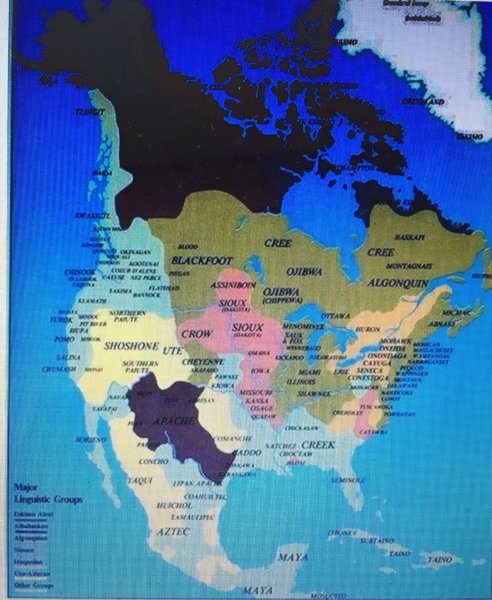

I often see maps of Indian territories pop up on the net. I like them. And then again, I don’t. I’ve seen also some of these same maps in classrooms and academic papers. In such cases, the narrative usually does a bit more to put the visual presentation in context, but on the net, that visual is often all you get.

I often see maps of Indian territories pop up on the net. I like them. And then again, I don’t. I’ve seen also some of these same maps in classrooms and academic papers. In such cases, the narrative usually does a bit more to put the visual presentation in context, but on the net, that visual is often all you get. I found this little gem to the left on twitter, at least I believe that’s where I got it. It’s pretty cool, really. It definitely matches my general sense of where various people should be. But then again, my general sense of where everybody should be rests on a skewed timeline. I expect them to be in certain places when the stories I read or tell about them in history class take place. So, if the different natives peoples are in the right place on cue for the historical narratives I expect to feature them, then the map matches my initial expectations, and I end up saying stuff like “it’s pretty cool.” The whole thing almost works, but it doesn’t take too many questions to bust up both those expectations and the maps that go with them.

I found this little gem to the left on twitter, at least I believe that’s where I got it. It’s pretty cool, really. It definitely matches my general sense of where various people should be. But then again, my general sense of where everybody should be rests on a skewed timeline. I expect them to be in certain places when the stories I read or tell about them in history class take place. So, if the different natives peoples are in the right place on cue for the historical narratives I expect to feature them, then the map matches my initial expectations, and I end up saying stuff like “it’s pretty cool.” The whole thing almost works, but it doesn’t take too many questions to bust up both those expectations and the maps that go with them.

This is one reason I like this map by

This is one reason I like this map by  One additionally interesting feature of Carapella’s maps is the fact that he leaves off the territorial boundaries. The names of each people simply appear on the map without any clear sense of the boundaries around them. We are left to imagine the full extent of each native territory. This avoids one of the larger problems one commonly finds in maps of Indian territory, their tendency to construe that territory in terms comparable to that of nation states. We all know the convention, color-coded spaces with clear boundaries between them. This conveys both a sense clear boundaries between different Indian peoples and a sense of homogeneity within those boundaries. Every part of Cherokee territory on such a map is just as Cherokeeish as any other part. They are all equally blue, or yellow, or mauve. One gets the sense that someone could pinpoint the exact moment they stepped into (or out of) Cherokee land, or that of any other tribe. We can practically see someone stopping on a dime, just like the cops in an old outlaw trucker movie do when they reach state lines. That’s how modern nation states work. It isn’t clear that this is now native territories work(ed).

One additionally interesting feature of Carapella’s maps is the fact that he leaves off the territorial boundaries. The names of each people simply appear on the map without any clear sense of the boundaries around them. We are left to imagine the full extent of each native territory. This avoids one of the larger problems one commonly finds in maps of Indian territory, their tendency to construe that territory in terms comparable to that of nation states. We all know the convention, color-coded spaces with clear boundaries between them. This conveys both a sense clear boundaries between different Indian peoples and a sense of homogeneity within those boundaries. Every part of Cherokee territory on such a map is just as Cherokeeish as any other part. They are all equally blue, or yellow, or mauve. One gets the sense that someone could pinpoint the exact moment they stepped into (or out of) Cherokee land, or that of any other tribe. We can practically see someone stopping on a dime, just like the cops in an old outlaw trucker movie do when they reach state lines. That’s how modern nation states work. It isn’t clear that this is now native territories work(ed).

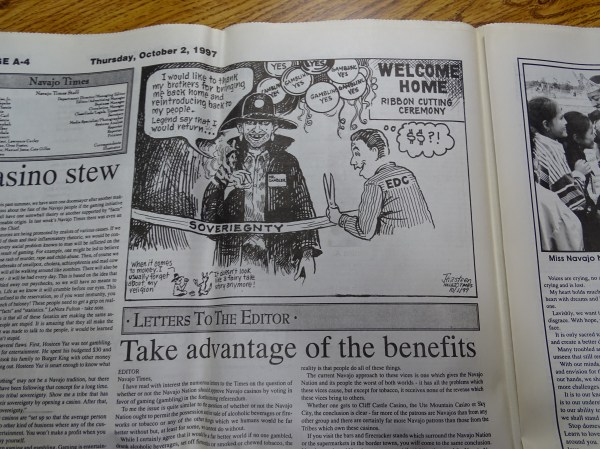

One of the most fascinating things about the debate over Navajo gambling in 1997 has to do with an aspect of Navajo origin legends. One of the greatest villains in these stories was a character, named

One of the most fascinating things about the debate over Navajo gambling in 1997 has to do with an aspect of Navajo origin legends. One of the greatest villains in these stories was a character, named